Get our independent lab tests, expert reviews and honest advice.

The deep web and how to use it

Anytime you want to find something on the internet, you generally turn to your web browser or a search engine like Google, Bing or DuckDuckGo. But there’s a whole world of other information available to you on the deep web (and it’s not the shady place you might think it is).

On this page:

- What is the surface web?

- What is the deep web?

- What is the dark web?

- How you can use the deep web

- Find academic articles with the Directory of Open Access Journals

- Look up old newspaper articles with Elephind

- Access inter-library loans with WorldCat

- View historical web pages with The Wayback Machine

Generally speaking, there are three ‘layers’ of the web: surface, deep and dark. The first two you’re already familiar with, but you’d need to go out of your way to visit the third.

What is the surface web?

The surface web is one of several names for any content directly accessible via a general purpose search engine like Google, Bing or DuckDuckGo. This means it turns up in search results and you can open it without any further effort.

While you might think of this as the majority of what you can access online, it actually only makes up an estimated 4% of web content worldwide.

Imagine what you’re missing out on by sticking to web search results.

What is the deep web?

The deep web makes up an estimated 90% of the web. It’s everything that isn’t indexed by general purpose search engines, or which isn’t directly accessible from search engine results.

This content includes things like social media posts hidden behind privacy controls, your emails, banking, and anything a website operator would rather search engines not focus on, among many other things.

It can also mean you need to visit a website that has an indexed homepage (and which can therefore be found via web search), but the rest of its content isn’t indexed and can only be found by using the website’s own built-in search function.

There’s nothing inherently shady about unindexed content. The members ‘My Account’ page on the CHOICE website, for example, isn’t indexed by web search engines and is only accessible via login credentials for privacy and security reasons.

The other major part of the deep web – things that can’t be directly accessed via search results – can include content behind a pay wall or anything that requires registration to view it (and therefore isn’t available with a single click, even if creating an account is free).

What is the dark web?

The dark web is a term loosely reserved for online networks focused on anonymity, which require special credentials or software to access. As a result, it’s often used for illegal purposes and can be extremely dangerous without the proper security measures.

Content on the dark web can range from benign to abhorrent to organised criminal activity. Think of it as a part of town where everyone wears a disguise and there’s little to no law enforcement.

But the dark web can also be used for legitimate purposes such as whistleblowers conversing with journalists, informants contacting authorities, or activists working against authoritarian governments.

Content on the dark web can range from benign to abhorrent to organised criminal activity

And it can simply be a haven for people who place an extremely high value on privacy, or for private networks based on peer-to-peer communication, among other things.

The dark web makes up about 6% of the web and can’t be accessed by a regular browser. Depending on the website or content you’re after, you need a browser that can access whichever ‘darknet’ is hosting your content, the most common of which is Tor.

The Tor network is a free, VPN-like system that anonymises your online activity and can be easily accessed via the Tor Browser (Edward Snowden is one of its more famous supporters). This Tor pre-requisite helps protect the identity of all parties during any exchange of data.

But the Tor network isn’t a fool-proof solution. At minimum, a VPN and stringent security software should also be used when browsing the dark web. But it’s best left alone completely unless you know what you’re doing.

How you can use the deep web

Given the deep web’s extensive breadth, it has a lot to offer if you know where or how to look.

A lot of deep web content is available on websites that themselves are findable via a web search, but the exact content you want is not. For example, you can easily find a website that hosts academic content on Google, but its original articles must be searched for via the website’s own search function. If you’ve ever wondered where people find those ‘recent studies’ that turn up in news headlines, this is a good place to start looking.

You’ve probably encountered plenty of websites structured in this way, but it’s easy to forget about non-indexed content and get search engine tunnel vision when you’re online.

It’s easy to forget about non-indexed content and get search engine tunnel vision when you’re online

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t use search engines to find easy answers. But if you’re looking up information on a specific topic, you can get additional results by doing a second, more general search for websites that host what you need, but which don’t index it.

Using those ‘recent studies’ as an example, a web search will probably bring up a lot of results, much of which will either be the same information bouncing around an echo chamber, or be conflicting readings of the source material.

If you’re keen on getting to the bottom of the matter, your second web search might be “free, peer-reviewed academic journals”. This broader search term could lead you to a website whose search function covers an array of unindexed information on the topic you’re after.

Below we look at a few ways you can use the deep web to find everything from historical newspaper articles to snapshots of how websites looked in years gone by.

Find academic articles with the Directory of Open Access Journals

Many academic journals charge for access to a full article or paper, but none of that money goes to the author or authors of the work. As such, quite a few academics are happy to share their published work for free – though sometimes with copyright restrictions – via open access journals.

The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) lets you search for content across almost 17,500 peer-reviewed, open access journals spanning more than 7.5 million articles. The website (doaj.org) can be found via a regular search engine, but its journals and articles are generally unindexed, so you need to find them via the DOAJ search function. This means the DOAJ homepage is surface web, while the articles themselves are deep web.

As a side note: if there’s a specific piece of work you’re unable to find for free online, despite trawling the deep web, you could try (politely) contacting the author directly via their professional contact details. They might be happy to send you the article or paper directly, although it’s entirely up to them, and they might not be able to if they don’t have exclusive rights.

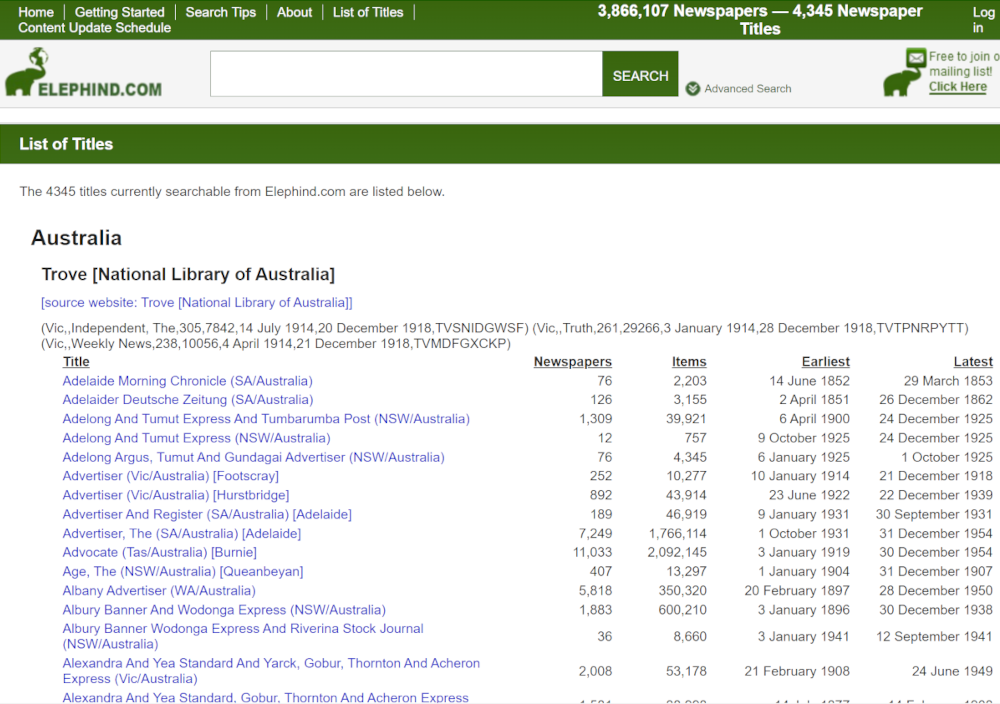

Look up old newspaper articles with Elephind

Need to look up an old newspaper article from 10, 50 or even 100 years ago? Elephind is an archive of historical newspapers from around the world with more than 200 million items across 4345 newspaper titles, including millions from Australia.

You can restrict searches based on years, such as 1800–1815, by the submission source (colleges, universities and libraries), and by text search restrictions such as headline only, including/excluding user comments, and all text.

Click Browse the newspaper archives to view all publications, separated by country. Australia’s section alone contains almost 700 separate newspaper publications, most of which have at least thousands of articles each, and all of which show the span of years they cover.

Access inter-library loans with WorldCat

Many libraries, especially larger ones, have inter-library loan agreements. So if your local or academic library doesn’t have a book, you might be able to find it elsewhere and have your library borrow it on your behalf.

WorldCat lets you search for titles across thousands of libraries at once – although you’ll likely get the best results if you keep it Australia-specific.

There are a variety of filters and search techniques you can use to refine your results, some of which are only available if you create a free website account. We suggest looking up a how-to video before you dive in, as the range of features is wide and the user interface is a bit outdated.

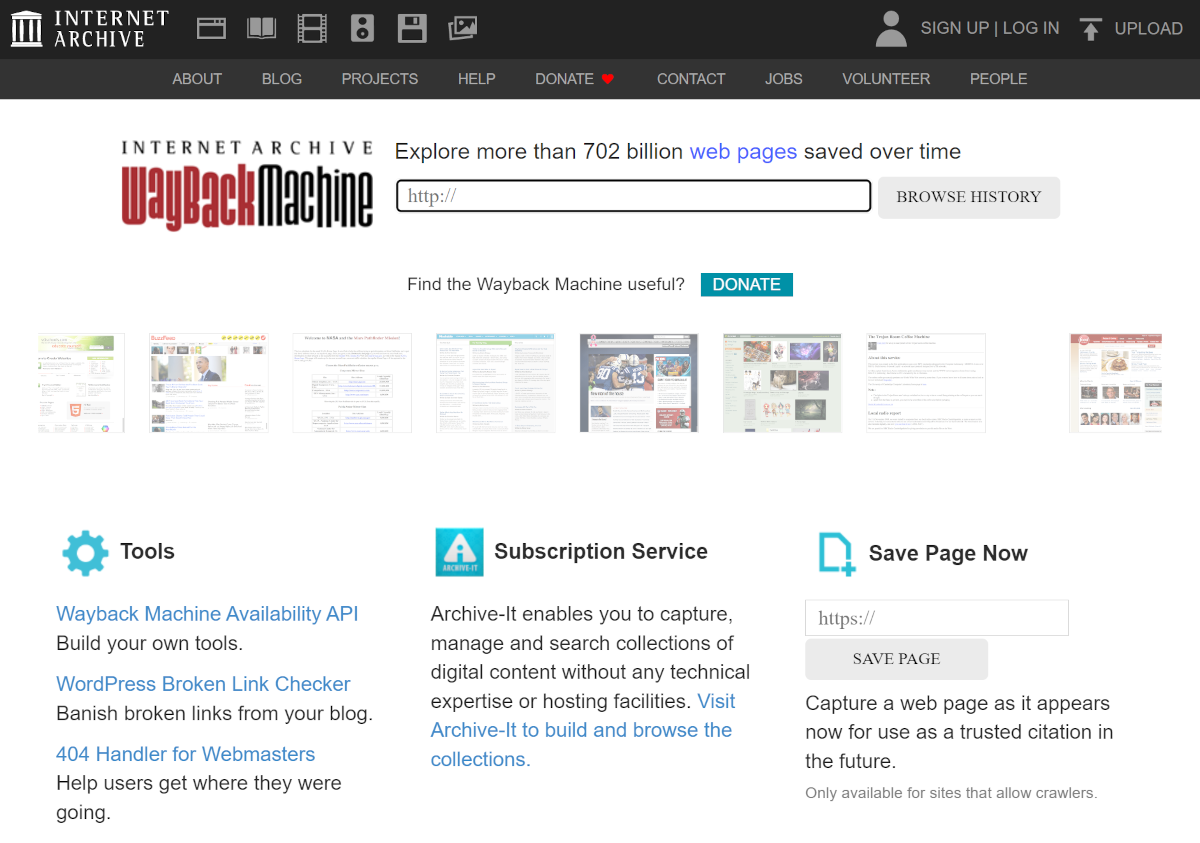

View historical web pages with The Wayback Machine

The Wayback Machine is a vast back catalogue of web pages, saved as they appeared at various points in time.

Given it would be problematic if past versions of websites turned up when you searched for the current one, these archived websites and pages are all unindexed.

The Wayback Machine can be useful for proving your case if a webpage erases or changes important content, but it can also just be fun to browse back in time and remember what the web used to look like (albeit without most of the embedded images).

CHOICE’s earliest snapshot is from 12 December 12 1998, which is certainly a blast from the past and not too shabby (if we do say so ourselves) given less than half of Australians were regular internet users even in the early 2000s.

A wide new world

General purpose search engines such as Google, DuckDuckGo, Bing and the rest are a great way to navigate the web, but keep in mind they only give you direct access to a tiny part of it. While using specific search phrases will often turn up results, you can find a lot more on the deep web if you know where or how to look.

The next time you’re looking for something online, consider other ways the information might be found.

Google can’t take you everywhere, but it can often point you in the right direction by taking you to a homepage with its own internal search function, a special interest forum, or to articles listing places where you can find the information, communities or other content you seek.