Get our independent lab tests, expert reviews and honest advice.

Extending the shelf life of fresh food

The shelf life of a food is the length of time a food can keep before it begins to deteriorate or, in some cases, before the food becomes less nutritious or unsafe. A range of traditional methods for extending the shelf life of foods have been successfully used for decades, and in some cases thousands of years – think salt curing, smoking, pickling, freezing, commercial sterilisation and canning, or the addition of chemical preservatives.

On this page:

The benefits of an extended shelf life for manufacturers are wide-ranging: the product can remain on sale on the shelf for longer, wastage and product returns from the retailer are reduced, more extensive product distribution is possible and highly seasonal products can be stockpiled, to name just a few.

But more often it’s fresh foods, rather than frozen or shelf-stable (ambient) foods, that are favoured and valued by consumers – and therefore by retailers. And consumers don’t want preservatives or other additives used to make these fresh foods safe and stable.

Keeping food chilled is essential (ideal storage temperatures are 5°C or less). But there are ways of processing or packaging fresh foods that will add extra days, weeks and sometimes even months to their refrigerated shelf life.

Processing methods

Flash pasteurisation

Flash pasteurisation, also known as high-temperature short-time (HTST) processing, is a process used on perishable beverages like fruit and vegetable juices and milk. It’s based on the same principles as traditional pasteurisation, using heat to kill food spoilage microbes such as bacteria, yeast and mould (see When foods go bad). But as indicated by the name, it uses higher temperatures for shorter times – milk, for example, is held at a minimum of 72°C for 15 seconds. The liquid is then cooled quickly and poured into sterile containers.

Flash pasteurisation is thought to cause less damage to the nutrient composition and sensory characteristics of foods (eg flavour and smell) than the more traditional low temperature long time pasteurisation treatments. But unlike UHT, flash pasteurised products still require refrigeration to prevent further growth of microbes.

In the chilled juice market, flash pasteurisation is sometimes used in conjunction with preservatives to extend shelf life. But some flash pasteurised products, Nudie juices for example, are preservative-free. Yet we’ve seen some in our local supermarket’s chiller with a shelf life of six weeks – a significant advance on the roughly 2 or 3 days for juice you squeeze at home.

High pressure processing

High pressure processing (HPP) is where pressures of up to 700MPa (7000 times the pressure of the atmosphere) are applied to food for a short time to inactivate microbes.

HPP has several benefits over heat treatments. It doesn’t disrupt chemical bonds, so this results in a product that generally has a far fresher taste, crisper texture, higher nutritional value and fresher colour compared with thermally processed counterparts, according to the CSIRO. Its research has shown that the quality and nutritional value of HPP juice is similar to fresh juice and consumers couldn’t pick out differences in appearance or taste between HPP orange juice and juice that was freshly squeezed.

The process also significantly extends the shelf life of food. In our local supermarket fridge we saw Preshafruit juices, which are HPP treated and preservative-free, with a shelf life of six months, for example.

The process, however, is expensive. To date in Australia, HPP has been used successfully in fruits and juices, ready-to-eat meats and guacamole – and most of these are high value, specialised products attracting premium prices.

Packaging methods

Different packaging methods generally achieve an extended shelf life for food by removing or reducing oxygen from around the surface of food. Lowering the amount of oxygen slows down and inhibits the growth of any bacteria on food. It also minimises oxidation – the process which can cause fat-containing foods like meat to go rancid or cut apple to turn brown, for example.

Vacuum packaging

Although it’s just one of many companies that produce vacuum shrink bag packaging, the name Cryovac is often synonymous with the process. In the 1960’s the Cryovac organisation and a US meat company joined in the concept of breaking down, vacuum packing and transporting primal and subprimal cuts of meat, rather than shipping in hanging carcass form.

In this process, almost all the air is removed prior to the final sealing of the pack, which must be made of plastic materials that retain the vacuum and have low permeability to oxygen. Myoglobin, the principle natural pigment in fresh meat, goes darker in the absence of oxygen, which is why vacuum packed meat can be purple in appearance (although the colour reverts to red when exposed again to air).

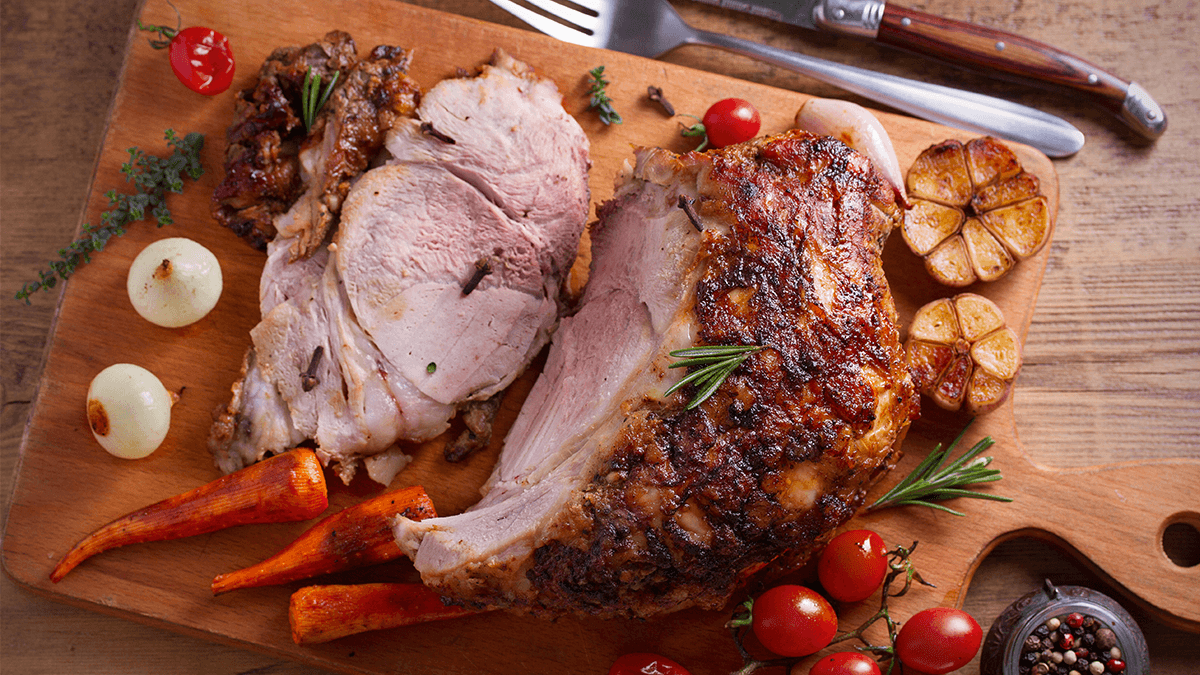

The shelf life of vacuum packaged fresh meat can run to months – more than four months (120-140 days) for beef, for example – although this is in cold storage conditions with temperatures close to freezing. The retail display life of fresh meat in the supermarket fridge is generally shorter – the longest we saw was just shy of three weeks for a leg of lamb – although it’s more than the 3-5 days expected shelf life of fresh meat stored in the fridge at home.

Modified atmosphere packaging

Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) is food packaging in which the composition of the air surrounding the food in the package is changed. The main gases used in MAP are oxygen, carbon dioxide or the inert gas, nitrogen.

The MAP technique is particularly useful for products that won’t stand up to hard vacuum or that tend to spoil or change colour in low oxygen situations. Gas mixtures can be adjusted so that there’s adequate carbon dioxide to inhibit the growth of microbes but also sufficient oxygen for meat to retain an appealing red colour, for example.

MAP can be used with various fresh or minimally processed foods, including meat, seafood, fruits and vegetables.

An additional piece of packaging technology which can be incorporated after removing most atmospheric oxygen using vacuum or MAP, and further extend shelf life, is an oxygen scavenger. Commonly in the form of a small sachet containing iron-based compounds and a catalyst, it removes the residual oxygen within the package.

Check the pack

When buying foods in MAP or vacuum packs, as with any packaging, it’s important to choose products that are tightly sealed, and avoid leaking packages.

Interpreting the date marks on food

Date marking gives us a guide to the shelf life of a food, and is based on either quality attributes of the food or health and safety considerations – it indicates the length of time a food should keep before it begins to deteriorate or, in some cases, before the food becomes less nutritious or unsafe. In Australia there are two main types of date marking:

- A ‘best-before’ date is the last date on which you can expect a food to retain all of its quality attributes, provided it has been stored according to any stated storage conditions and the package is unopened. Quality attributes include things such as colour, taste, texture, flavour and freshness. A food that has passed its ‘best-before’ date may still be perfectly safe to eat, but its quality may have diminished.

- A ‘use-by’ date is the last date on which the food may be eaten safely, provided it has been stored appropriately and the package is unopened. After this date, the food should not be eaten for health and safety reasons.

The Australian Food Standards Code outlines which dates apply to different foods, and gives guidance to manufacturers on how to calculate the shelf life.

When foods go bad

If a food hasn’t been handled, processed, packaged or stored correctly, or you keep it past its use by date, there’s a chance it will be contaminated with bacteria. Some bacteria cause food to spoil – becoming slimy with off odours and flavours – but these spoilage bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, are generally harmless.

Food poisoning bacteria on the other hand don’t always change the smell, taste or appearance of food, but if consumed can make you very ill. Common food poisoning bacteria include Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, Staphylococcus aureus, certain strains of E coli and Listeria monocytogenes – the latter presents a particular hazard for pregnant women and their unborn babies, the elderly and people with compromised immune systems.

In 2015, 16% of all government food recalls in Australia were due to microbial contamination.

What’s UHT?

Ultra-high temperature (UHT) processing heats food to very high temperatures (130-150°C) for a short time, often for only a few seconds. It’s most commonly associated with milk (although it’s also used for products including fruit juices and soups). UHT treatment can impart a cooked flavour to milk. But if packaged under sterile conditions, UHT milk is shelf stable and can be stored for months without refrigeration – although it must be chilled once opened.