Get our independent lab tests, expert reviews and honest advice.

How bad are trans fats in food?

Trans fats, also called trans fatty acids, can be seriously bad for your health. Eating particular types of trans fats can put you at risk of heart disease, and so significant is the problem that the World Health Organization (WHO) is calling on governments worldwide to eliminate industrially produced trans fat from the food supply by 2023.

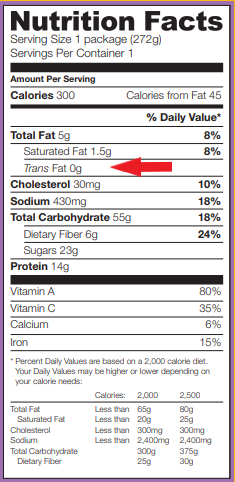

In Australia there’s no requirement for trans fats to even be labelled on food. So should we assume they’re not an issue for us here?

Our verdict: trans fat should be labelled, at minimum

- There’s no safe level of industrially produced trans fat. They have no known health benefits and, importantly, they can be replaced by healthier alternatives in foods without affecting their consistency, taste or cost.

- A mandatory limit on industrially produced trans fat in foods or a ban on the use of partially hydrogenated oils are the most effective ways to reduce or remove trans fat from the food supply. These options also have the greatest potential to reduce heart disease risk, particularly for the most disadvantaged groups of people. But in the absence of either of these actions, CHOICE would like to see trans fat labelled.

- Labelling trans fat would allow people to make an informed decision about what they’re buying. And there’d be more incentive for manufacturers to reformulate foods and replace partially hydrogenated oils with healthier alternatives – particularly if consumers choose to avoid products that contain them.

What is trans fat, and why is it bad for us?

Trans fats occur naturally in some ruminant animal products including butter, cheese and meat. But the trans fat of concern (chemical name is elaidic acid) – the one that’s the focus of this article – is formed when liquid unsaturated vegetable oils are partially hydrogenated or ‘hardened’ during processing.

Known as ‘industrially produced’, ‘manufactured’ or ‘artificial’ trans fat, it’s common in baked goods, pre-packaged foods and some oils used for commercial frying.

Industrially produced trans fat increases levels of ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol in our blood – a major risk factor for heart disease

Partially hydrogenated oils have been popular with the food industry because they help crisp up products when heated (think pies, pastries, chicken nuggets, croissants and the like) and have a longer shelf life than most other fats.

Industrially produced trans fat is bad for us because it increases levels of ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol in our blood – a major risk factor for heart disease – and decreases levels of ‘good’ HDL cholesterol.

This type of fat also has adverse effects on other risk factors for heart disease. According to the WHO, diets high in trans fat increase heart disease risk by 21%. It estimates that every year globally, trans fat intake leads to more than 500,000 deaths of people from cardiovascular disease.

How much trans fat is in our food?

It’s obvious we should steer clear of trans fat. But how much is in the food we eat anyway?

The food industry says that trans fat was largely removed from the Australian food supply during the 1990s, and points out that Australian soft margarines – once a major source of trans fat – have been trans-fat free for over 10 years.

In 2013 our food regulator, FSANZ, carried out a survey of the trans fat content of New Zealand and Australian foods. This was in response to a 2011 labelling review, which recommended the mandatory declaration of all trans fatty acids above an agreed threshold in the nutrition information panel if industrially produced trans fat hadn’t been phased out of the food supply by January 2013.

FSANZ tested a total of 500 samples from 39 different product categories. It reported that – excluding those likely to contain ruminant trans fat – approximately 86% of the samples had trans fat concentrations below 2% of total fat content, the limit adopted by many countries (see Action on trans fat worldwide), and that the results were generally consistent with those seen in a survey five years earlier.

On the surface these numbers sound reassuring, but put another way, that’s 14% of samples with trans fat levels above that limit.

The worst offending product categories were croissants, prepared pastry, vegetable oils, edible oil spreads and custard baked goods. Ideally we’d avoid the high trans fat products from these and other categories, but as trans fats aren’t even labelled, that’s easier said than done (see our tips for how to limit your intake).

Without constant surveillance these fats could seep back in to our food supply

The food regulator also surveyed 52 food companies and suppliers who provide oils to fast food and quick service restaurants. The 22 companies that answered all said they were reducing or planning to reduce the trans fat content of their products. But more than half the companies that FSANZ contacted didn’t respond.

Ultimately FSANZ concluded that mandatory labelling wasn’t warranted. But public health nutritionist Dr Rosemary Stanton, for one, isn’t comfortable with the status quo.

“I’m concerned that without constant surveillance and in the absence of requirement to label industrially produced trans fat in most products, these fats could seep back in to our food supply,” she says. And that’s assuming they were removed in the first place. Results of our trans fat spot test (below) lends some weight to her concern.

Trans fat spot test

To see if there’s trans fat still lurking in our food, we bought just a handful of products – selected for their relatively long shelf-life and high total fat content and non-descript ‘vegetable fat’ or ‘vegetable oil’ high up in the ingredients list – and, holding our breath, sent them to the lab for analysis. The results are as follows:

| Product | Trans fat / 100g | % of total fat content |

|---|---|---|

| Four’n Twenty Party Sausage Rolls | 0.7g | 4.3%* |

| Sargents Traditional Meat Pies | 0.2g | 1.4% |

| Doritos Cheese Supreme | 0.1g | 0.5% |

| Cadbury Mini Rolls | 0.1g | 0.4% |

| Toscano French Croissants | 0.1g | 0.4% |

| Betty Crocker Creamy Deluxe Frosting | 0.1g | 0.4% |

We reached out to Patties, the producer of Four’n Twenty products, and asked if they have plans to label trans fat, but didn’t receive a response.

Are we eating too much trans fat?

FSANZ tells us: “Monitoring of trans fats in the Australian and New Zealand food supply has consistently found that Australians obtain on average 0.5% of their daily energy intake from trans fats and New Zealanders on average 0.6%. This is well below the WHO recommendation of no more than 1%. It is also below the levels in many other countries.”

Stanton argues that the problem with averages is that they ignore significant minorities – in this case, subgroups of people who likely already suffer from health issues related to poor diet.

The majority of Australians may have a trans fat intake of less than 1% of total energy, but according to a 2017 analysis of the national nutrition survey done by the Sax Institute for the Heart Foundation, around 10% of Australians – that’s potentially 2.5 million people – continue to have an intake exceeding this level, and these people are more likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Researchers found that 14.2% of people with the lowest level of income, and a similar percentage of people with the lowest level of education, exceeded the 1% WHO trans fat intake cut-off.

Eating a meat pie, a custard baked good and some popcorn in a day could get you up to 7g of trans fat

Even small amounts of trans fat in individual products can add up over the course of a day, and the issue is compounded if you’re eating high trans fat foods on a regular basis.

The Sax Institute report demonstrates that eating a meat pie, a custard baked good and some popcorn in a day could get you up to 7g of trans fat, if those foods happened to be the high trans fat samples identified in FSANZs survey. That’s around 3% of daily energy intake – three times the WHO-recommended limit. For some people, a diet like this could be fairly typical.

Our case study demonstrates how vulnerable consumers can be more exposed to high trans fat foods.

Case study: Vulnerable consumers need protection

Professor Amanda Lee spends a fair chunk of her time working with Aboriginal communities to help improve health. One thing she does is monitor the food products sold in remote stores, trying to ensure that the relatively limited choices available are the healthiest options.

While working as a consultant for an Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation a few years back she noticed a cheap bulk pack of margarine being sold that had a positive sounding ‘cholesterol-free’ claim on pack. Under the Food Standards Code this triggered inclusion of trans fat content on the nutrition information panel, which was alarmingly high.

This cheap, high-trans-fat product was being sold in stores in remote communities to people already vulnerable to high rates of heart disease

“I contacted the manufacturer directly, and they confirmed that it contained 5g trans fat per 100g. When I asked why they were producing it, they told me ‘because it’s cheap, and only used for catering and export'”. Worryingly, this cheap, high trans fat product was being sold in stores in remote communities to people already vulnerable to high rates of heart disease.

Lee subsequently found the same margarine in two other supermarkets in low-socioeconomic areas in Queensland, so she followed up with a letter to the company.

“I never received a reply, but the margarine was removed from the company’s website a few months later,” she says.

Ever since, Lee has had concerns about the sampling framework used in available trans fat surveys in Australia and the potential for other high trans fat products to exist in our domestic and export food supply.

Now Professor of Public Health at The University of Queensland, she is preparing to analyse suspicious foods for trans fat, targeting different locations and products from those sampled by FSANZ in 2013 .

“In the meantime, I’d like to see trans fat content included in all nutrition information panels to ensure all consumers are aware of any problems,” Lee says.

How can I avoid trans fat?

It’s difficult to avoid trans fat if you can’t check on the label to see how much, if any, is in the foods you eat. But there are a few things you can do to limit the amount of industrially produced trans fat in your diet:

- Eat less commercially prepared baked foods (cakes, biscuits and pastries), snack foods, and deep fried fast foods.

- Avoid using solid vegetable cooking oils (shortening).

- Check the ingredients list of packaged food products for ‘partially hydrogenated vegetable oils’ and avoid foods that contain them – particularly if they’re near the top of the list.

- Fill your diet with foods from the core food groups recommended in the Australian Dietary Guidelines: vegetables and legumes, fruit, grain (cereal) foods, lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans and milk, yoghurt, cheese and/or their alternatives – the less processed, the better.

Action on trans fat worldwide

Since the WHO’s announcement of its campaign to eliminate trans fat from the food supply by 2023, many countries have set mandatory limits on industrially produced trans fat or banned partially hydrogenated oils in food production. A recent report from the Non Communicable Disease (NCD) Alliance says mandatory trans fat policies have now been enacted by 55 countries and territories in all WHO regions, 31 of which have already been implemented.

Denmark was the first country to act on trans fat in the food supply, passing a law in 2003 limiting industrially produced trans fat content in all foods to 2% of fats and oils, and a number of other countries, including Austria and Singapore, have followed suit.

Some countries, including India and Switzerland, limit the trans fat content in the fats and oils only, including those used by companies to make prepared foods.

Canada and the US have both implemented nationwide bans on partially hydrogenated oils, the main source of industrially produced trans fat. And many of these and other countries require trans fat to be labelled on packaged food.