Get our independent lab tests, expert reviews and honest advice.

What is the Health Star Rating system?

Health Star Ratings (HSR) have been appearing on food labels since 2014. The fundamental purpose of the HSR system, according to the Health Star Rating website, is ‘to assist consumers to make informed food purchases and healthier eating choices’.

On this page:

- How Health Star Ratings are displayed

- How Health Star Ratings are calculated

- What about daily intake labelling?

- CHOICE verdict

But while the system is voluntary and has a few limitations, it will only be truly helpful for consumers if most (if not all) food and drink companies get on board and apply ratings to all applicable products.

How Health Star Ratings are displayed

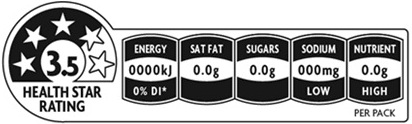

There are three main elements of the HSR system graphic:

- Health Star Rating (both as a star rating graphic and number, calculated per 100g/mL of the food)

- Energy icon (per 100g/mL, pack or serve)

- Nutrient icons – three ‘negative’ nutrients (sat fat, sugars, sodium) plus one optional ‘positive’ nutrient such as fibre or calcium (per 100g/mL, pack or serve)

Companies are encouraged to use as many elements of the graphic as possible, following a hierarchy of options laid out in the Style Guide, subject to available pack size and label space.

How Health Star Ratings can help

Making healthy food choices can be difficult, particularly when faced with the many claims frequently made on products. Products claiming to be low fat are often packed with sugar and high in kilojoules. And claims of added vitamins and minerals can be masking a product with few other redeeming nutritional features.

The Health Star Rating system, which was developed by the government jointly with food companies, consumer groups and NGOs, addresses this.

The system ranks food products on a scale from half a star (least healthy) to five stars (most healthy), allowing you to make healthier choices at a glance. And the calculator behind the system reflects the Australian Dietary Guidelines, the best, most current dietary advice available to consumers.

The system does have its limitations, however.

1. You can’t compare apples with oranges

Instead, HSRs should be used to compare like with like – think similar products that are side-by-side on the supermarket shelf.

If you’re choosing a staple such as bread, for example, one with more stars should be a healthier option than the one next to it with less. And even when it comes to processed treats or snack foods like a bag of chips, you can still make healthier choices by choosing an equivalent product with more stars on its label.

Just don’t use the stars to compare chips with bread.

2. It won’t help you determine ‘naturalness’

Food additives are a major concern for many consumers, and one criticism of the system is that it doesn’t take them into account. A product like margarine which generally contains multiple ingredients including various additives can have a higher HSR than butter, which is minimally processed and has just a couple of ingredients, for example.

The HSR System, however, was designed to interpret nutrient information and give you an overall picture of the nutritional profile of a food, not to judge how ‘natural’ or ‘pure’ a product is.

Including additives in the algorithm that produces the ratings would be very difficult, as well as change the purpose. The best way to determine the naturalness of a product is by looking at the ingredients list.

3. It’s not applicable to all foods

The HSR system was designed to be used on packaged food products – a good rule of thumb is that if the food product has a nutrition information panel (NIP), it can have a health star rating.

Products exempt from NIP labelling, and therefore the expectation of HSR labelling, include:

- fruit, vegetables, meat, poultry, and fish that comprise a single ingredient or category of ingredients

- foods with inherently low nutritional contribution, such as herbs, spices, vinegar, salt, pepper, tea and coffee

- fresh, ‘value-added’ products, such as packaged fruit, vegetables, meat, poultry and fish, and pre-packaged rolls and sandwiches (although products can carry HSR labelling if label space permits and the products are of standardised composition, such as bulk-produced pre-packaged sandwiches, rolls or wraps)

Additionally, health star ratings shouldn’t be displayed on special purpose foods such as infant formula and food, toddler milks, formulated supplementary sports food or alcohol.

How Health Star Ratings are calculated

The rating is based on an algorithm which firstly takes into account kilojoules plus three ‘negative’ (‘bad’) nutrients – saturated fat, sodium and total sugars.

These four aspects of a food – kilojoules, saturated fat, sodium and sugars – are the basis for the rating because they’re associated with increasing the risk factors for chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

This is balanced against the ‘positive’ aspects of a food – its fruit, vegetable, nuts or legumes content (all valuable sources of a range of vitamins, minerals and antioxidants), as well as the protein and dietary fibre content in some cases.

The data used for calculations is per 100g or 100mL of a food.

Why are HSR calculations based on per 100g/mL of food?

Research conducted to inform the HSR system found that consumers prefer nutrition information based on 100g/mL because of confusion over serving size. Moreover adults, children, males, females, more active or less active people may have different serving size requirements – serve sizes can over- or under-estimate the amount people should eat – meaning nutrition labelling based on serving sizes can be misleading.

A consistent measure like 100g/mL, on the other hand, allows consumers to compare products easily and accurately within categories – whether you’re choosing the healthiest fruit yoghurt or the healthiest frozen lasagne.

What about daily intake labelling?

CHOICE has long maintained that the industry-developed Daily Intake Guide (DIG), or % daily intake (%DI), thumbnail labelling fails to provide consumers with the necessary information to easily compare the nutritional content of similar products.

For starters it’s based on the daily energy intake of an ‘average adult’, so it’s not applicable to a range of consumer groups, including children. It’s also based on suggested serving sizes, which can be hugely inconsistent within product categories, making for unfair comparisons.

Our 2013 survey showed that 62% of Australians have either never heard of this scheme, or rarely use it to choose food products. And a national survey by research group IPSOS revealed that just 51% of the 3000 respondents found the DIG thumbnail graphic easy to understand, compared with 72% for the health star rating graphic.

Despite this, the Style Guide doesn’t object to its use, as long as it’s clear that it’s not linked to the HSR graphic.

CHOICE verdict

HSRs aren’t the be-all and end-all of healthy eating. However, they can certainly help you make healthier choices, particularly when faced with a range of similar-looking products making a range of appealing nutrient claims.

Not only can the HSR system help consumers directly, it provides an indirect benefit by incentivising companies who choose to apply it to improve the nutritional profile of products in order to achieve more stars.

But the system will only succeed – and benefit consumers – if there’s take-up from the majority of food companies. CHOICE applauds companies who are already on board, and we strongly encourage those companies that haven’t, to do so.