Get our independent lab tests, expert reviews and honest advice.

How much are you getting for your money? Unit pricing will tell you

Need to know

- As COVID-19 puts many Australians out of work, Consumer Affairs Australia & New Zealand has launched a campaign urging Australians to shop by unit pricing and save money

- Supermarkets have a shaky track record when it comes to abiding by unit pricing legislation

- You could save, on average, 26% by choosing the large rather than the medium-size pack

Tricky packaging and labelling are a big part of how supermarkets sell products these days. This tactic can make value-for-money comparisons hard to get your head around.

It’s not an issue with unpackaged products such as meats, seafoods, cheese, and fruit and vegetables, whose prices are based on a clear-cut dollar-per-kilogram approach.

But packaged goods come in a dizzying array of brands, shapes, sizes and colours that aren’t designed to make clear how much you’re getting per dollar spent.

That’s where unit pricing (or price per unit of measure) comes in. When clearly shown, it lets you look past the marketing and make easy comparisons.

Packaged goods come in a dizzying array of brands, shapes, sizes and colours that aren’t designed to make clear how much you’re getting per dollar spent

Aside from the confusing and hard-to-read signage at Australia’s supermarkets, the concept of unit pricing is straightforward.

Packaged groceries are often sold by weight, and liquids sold by volume. So if you find a 2kg packet of rice for $4.80, with a unit price of 24c per 100g, you could compare that with a different brand that sells 1kg in a box for $3, with a unit price of 30c per 100g. Assuming that one brand of rice is as good as another, the 2kg packet would be the better deal. (Larger package sizes often have lower prices per unit.)

And guess what? Large supermarkets including Woolies and Coles (or any store of more than 1000 square metres) have been required to give the unit price for packaged grocery items since 2009. They must do so for both in-store and online purchases.

The code requires that the unit price be:

- prominent – it must stand out so that shoppers can see it easily

- displayed close to the selling price for the grocery item

- legible – it must not be difficult to read

- unambiguous – the information must be accurate and its meaning clear.

Unit pricing still a work in progress

The 2009 legislation was a big win for consumers, but figuring out and comparing unit prices can still take some doing. And the retailers don’t make it easy. Unit prices are supposed to be prominent and legible, but they’re often not.

In 2018, for instance, Aldi reduced the font size of its unit pricing, making it significantly harder to read.

Far too many unit prices are difficult to read, and impossible for people who don’t have good vision or mobility

Ian Jarratt, Queensland Consumers Association

In a 2019 CHOICE survey, a quarter of respondents said they had trouble deciphering unit prices.

The Queensland Consumers Association’s (QCA) Ian Jarratt, who helped lead the campaign to introduce unit pricing in 2009, told us in 2019 that the legislation is failing consumers.

“The system simply isn’t doing a good enough job,” Jarratt said. “Far too many unit prices are difficult to read, and impossible for people who don’t have good vision or mobility.”

Now, as many consumers are forced to scrimp and save due to the COVID-19 crisis, the federal government is on the case.

Consumer Affairs Australia & New Zealand (CAANZ) launched a campaign to raise awareness of the issue on 22 September (it runs until 30 October). Here at CHOICE, we’ve long supported the use of unit pricing.

Top ten tips for shopping by unit prices

1. Brands

Compare the unit prices of different brands of the same product. Differences between brands are often large.

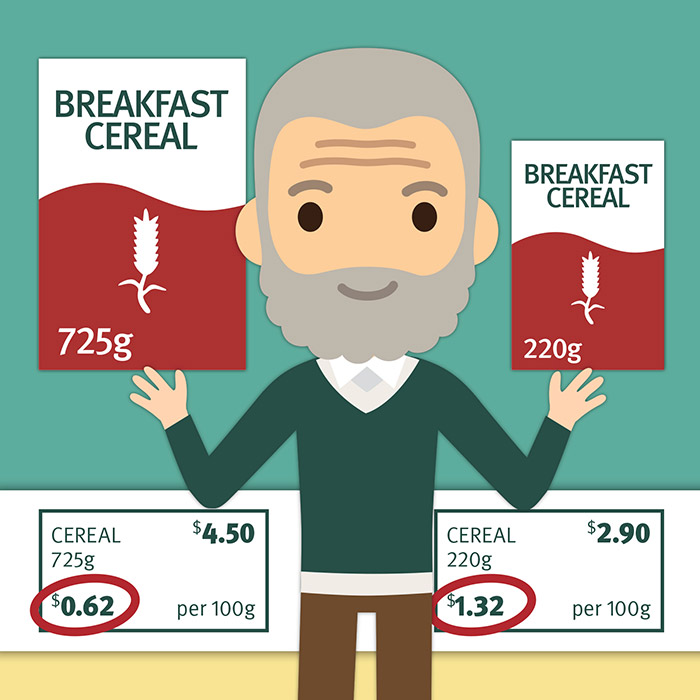

2. Pack sizes

Look at the unit price of other sizes of a brand and other brands.The unit price of large packs is usually much lower than small or medium size packs.

3. Special offers

Compare the unit prices of special offers with the regular price of the same product or with other brands and sizes. There may be an identical or similar product or another pack size available at an even lower unit price.

4. Loose or prepacked products

If a product is available loose or pre-packaged, check the unit price of both. Often the unit price of the loose product will be much lower than the packaged product.

5. Elaborate packaging

Compare the unit prices of products in elaborate packaging to those in simpler packaging. Generally, the simpler pack will have the lower unit price.

6. Sub-packs

If a product is available in sub-packs (for example individual portions/servings/sachets within a pack) as well as just in one pack, compare the unit prices of each. The unit price for the product in sub-packs is usually much higher.

7. Products in different forms

Check the unit prices of the same product when it is sold in different forms, for example fresh and frozen. The frozen product may have a lower unit price or you may be able to freeze low priced fresh product yourself.

8. Substitute and alternative products

Look for close substitutes for, and alternatives to, many products. Products that often have close substitutes or alternatives include fruit and vegetables, meat, fish, and cheese.

9. Products in several parts of a store

If a product is sold in more than one part of the supermarket, check the unit prices wherever the product is sold. There can be big differences in unit prices on products sold in different parts of a supermarket.

10. Unit prices at different stores

Compare the unit prices of products at different stores. Unit prices can vary greatly between stores.

QCA: Government funding long overdue

At the launch, Queensland attorney-general and minister for justice Yvette D’Ath reminded consumers of the supermarkets’ obligations.

“Large grocery stores and some online grocery retailers must display the unit price when selling food and other grocery products, such as bread, eggs, fruit and vegetables and toilet paper,” she said.

“Is a big pack of cereal more cost effective than a small pack for your family, or is a small pack of another brand on special this week better value? Unit pricing makes it easy for you to decide.”

The federal government needs to get a move on and complete and implement the review of the code that it started in November 2018

Ian Jarratt, Queensland Consumers Association

Commenting on the current campaign, Jarratt told CHOICE “we strongly support this campaign by the consumer affairs agencies. It’s the first government funded campaign since the start of compulsory unit pricing in December 2009 and long overdue.

“We know from Queensland University of Technology research that letting people know about the existence of unit pricing, and how it can be used to compare values, significantly increases use.

“Inadequate prominence and legibility are still big problems in stores and online. The federal government needs to get a move on and complete and implement the review of the code that it started in November 2018.”

Real savings for those who look

In an earlier investigation, the QCA proved that making the effort to find the unit prices and make the comparisons can really pay off.

According to the QCA’s findings at the time, fresh chillies can cost $125 per kg when bought in a 20g package, but only $9 per kg when bought loose.

A national brand of cornflakes can cost $1.13 per 100g in a small pack, but just 38c per 100g in a large pack.

One brand of paracetamol tablets in a 20-tablet pack can cost 16c per tablet, but another brand only 4c per tablet.

You don’t have to be a maths whiz to figure out that these kinds of price differences can have a major impact on your household grocery costs over the long term

When we spoke with Jarratt in September this year, he reported that rocket costs $12 per kg loose and $33 per kg for a small package at his local supermarket.

You don’t have to be a maths whiz to figure out that these kinds of price differences can have a major impact on your household grocery costs over the long term.

Sure, you may pick a product with a higher unit price because it tastes, feels or looks better – or is in a more convenient pack size – but understanding unit pricing is important if you’re keen on getting value for money.

How much can you save?

In a 2019 exercise, the QCA reduced the unit prices of 19 packaged national-brand items by an average of 26% by choosing the large rather than the medium-size pack.

And in 2018, a CHOICE shopping excursion found that choosing loose over packaged produce was cheaper for more than half (53%) of all purchases in the excursion, and that choosing the cheapest per-unit price could save shoppers at least $1600 a year.

The lesson? Focus on the unit price, not the selling price – and know where to find it on shelf labels and other price signs.

Supermarkets still thwarting like-for-like

Miniscule font sizes, inconsistent use of unit pricing and a lack of any unit price at all are bad enough. But, on top of all that, shoppers are often confronted by supermarket signage that lists different units of measurement on different pack sizes of the same product. This makes it that much harder to tell which package is giving you the most product for your money.

And pack sizes can be extremely variable, as we recently reported in our comparison of national brand prices at supermarkets.

Then there are online grocers that don’t include unit pricing because they don’t sell all of the 11 types of product listed in the unit pricing code. Others’ websites don’t let you sort products by their lowest unit price.